Graphs and Trees

Many methods of data analysis “branch out” (choose one possibility over another) and link pairs of objects based on similarity in some features (e.g., pairs of cities with a direct connection). The concept of a graph was invented to keep track of these processes and information structures. This concept is convenient for both analysis and programming.

Graphs

A graph is defined as two lists: 1) a list of objects–called nodes or vertices–and 2) a list of pairs of nodes–these pairs are called edges or arcs or links.

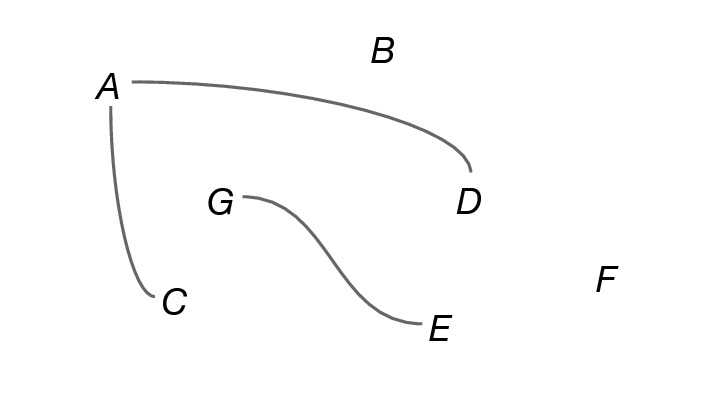

So, we can specify a graph by writing down these two lists–for example, nodes: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, links: {A, C}, {A, D}, {E, G}–but sometimes it is helpful to sketch the graph:

Another way to list the same links is: {C, A}, {A, D}, {G, E}. Any others?

A pair of nodes paired up by a link is said to be “linked”.

Walks, paths, and connectivity

Sometimes the links model transporting of objects or transmission of signals from node to node, and the transportation/transmission is possible only if the two nodes are linked.

If an object is transported through two or more nodes, then the nodes it traverses can be written down, in that order. A sequence of nodes in graph with every consecutive pair linked is called a walk (in that graph). A walk can have repeated nodes: after all, some itineraries go through the same location more than once.

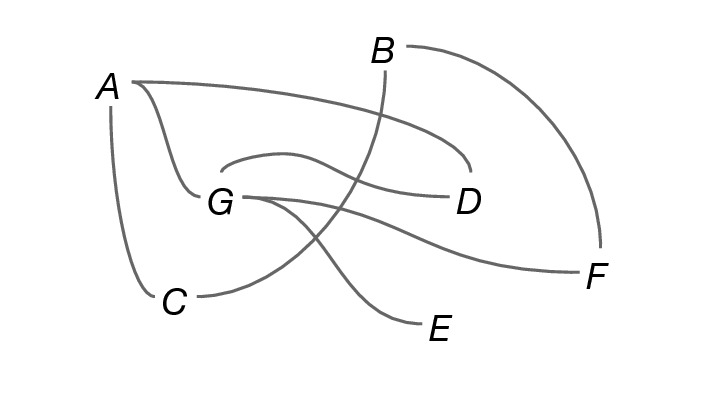

In the graph

the node sequence C, A, G, D, A, G, E is a walk (try to trace it with a pointer), the node sequence C, A, G, A, D is a walk, but the node sequence G, E, F, B is not a walk, since the nodes E and F are not linked.

A graph is connected if every two nodes are connected by a walk.

(A list of cities is connected if one can get from any city to any other in the list without visiting any city off the list. The “getting” from one city to another does not have to be direct: we can go through other, intermediate, cities, as long as they are on our list.)

Of the two graphs illustrated above, the first one is not connected, but the second one is.

Two special types of walks

Paths: A walk with each node appearing exactly once is called a path.

In the last graph above, the node sequence C, A, G, D, A, G, E is not a path, the node sequence C, A, G, A, D is not a path, but the node sequence C, A, G, F, B is a path.

Given a walk in a graph, one can always delete from it some vertices so as to obtain a path.

Cycles: A walk with the first and last node being the same one is called a cycle.

In the last graph above, the walk A, G, D, A is a cycle, and so is C, A, G, D, A, C.

One exercise in algorithms is to write a program that determines whether a given graph contains a cycle.

Trees

A connected graph with no cycles is called a tree. If one of the nodes in a tree is chosen and marked as “root” (it becomes clearer what actually to do with roots once one uses a tree in an algrithm), the resulting tree is a rooted tree.

Directed graphs

Sometimes graphs are needed to model links that can be traversed in one direction, but not in the other (like one-way streets). Such links are specified a little differently from the above; namely, one now writes a links as an ordered pair of nodes.

A graph where the links are ordered pairs of nodes is called a directed graph.

In a sketch of a directed graph, each link is usually shown with an arrowhead indicating the direction of the link. What if we want direct access both from node A to node B and from B to A? Answer: include both the links (A, B) and (B, A).